Almost two thousand years ago, Jews in the Galilee town of Huqoq prepared for revolts against the Romans by building a network of tunnels for hiding. Those conflicts turned tragic, ending with the Roman exile of the Jews. Yet later, a synagogue was built near the same hiding complex. It’s more than a tale of historical construction. It’s a message of hope—and it’s been recently uncovered by modern day Israelis, including soldiers.

“The hiding complex provides a glance on a tough period of the Jewish population in Huqoq and in the Galilee in general,” the excavation directors, Uri Berger of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and Prof. Yinon Shivtiel of the Zefat Academic College, were quoted as saying in an IAA press release. “However, the story that the site tells is also an optimistic story of an ancient Jewish town that managed to survive historical tribulations.”

While the revolts in 66-73 CE and 132-136 CE ended in Jewish defeat, Berger and Shivtiel note that the Huqoq archaeological site “is a story of residents who, even after losing their freedom, and after many hard years of revolts, came out of the hiding complex, and established a thriving village, with one of the most impressive synagogues at the area.”

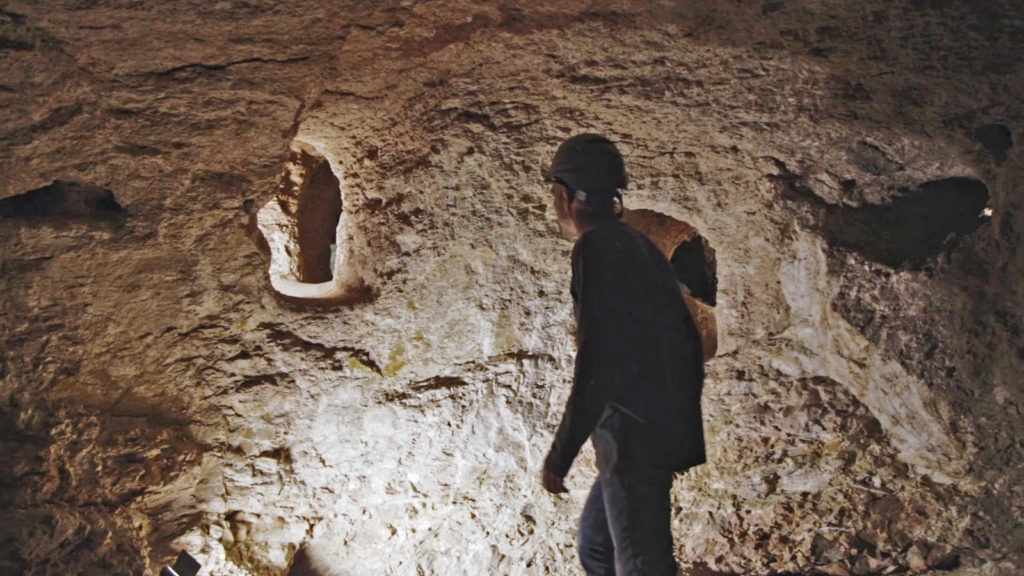

The tunnel complex, described by the IAA as “the largest and most impressive discovered at the Galilee”, has eight hiding cavities that includes a converted water cistern. Even a Jewish ritual bath (known as a mikveh) became an entrance to the network. Several of the tunnels enabled Jews to travel in low spaces under houses. The press release said the system’s tunnels were connected at 90 degree angles, “to hamper the heavily armed Roman soldiers chasing the rebels.”

A nearby hilltop is home to the synagogue, which was discovered in 2011 and has what the IAA press release called “impressive and unique mosaics, dating to the Byzantine period” (395-1453 CE).

The hiding complex excavation, which took place over the last few months, unveiled hundreds of broken clay and glass dishes, an “impressive ring”, and more. The findings help date the tunnel system to include the first revolt against the Romans in the first century and the decisive “Bar Kokhba Revolt” more than half a century later. While it’s unknown at this time if the tunnels were actually used in the latter Bar Kokhba revolt, Berger and Shivtiel said it appears to have been prepared for that use. They said in the press release, “We hope future excavations will bring us closer to the answer.”

In the meantime, the archaeological project is bringing Israelis closer together and bringing everyone closer to history. The IAA press release said the Huqoq tunnel project, funded by The Ministry of Heritage and in collaboration with the Zefat Academic College and KKL-JNF, was intended to eventually enable the site to be opened to the public and “to reveal the rich history of the site while involving the youth in its discovery.”

The excavation project included school students, volunteers from the Israel Cavers Club, and soldiers from the IDF underground operations unit. “We turned the excavation in the hiding complex into a community excavation as part of the Israel Antiquities Authority’s vision of connecting the public to its heritage,” Dr. Einat Ambar-Armon, director of the IAA Archeological-Educational Center in the Northern Region, said in the press release. And that communal goal is just the beginning.

As IAA Director Eli Escusido noted in the press release, “The Israel Antiquities Authority considers the Huqoq site and its various discoveries as part of a flagship project that will draw visitors from all over Israel and the world.”

(By Joshua Spurlock, www.themideastupdate.com, March 25, 2024)